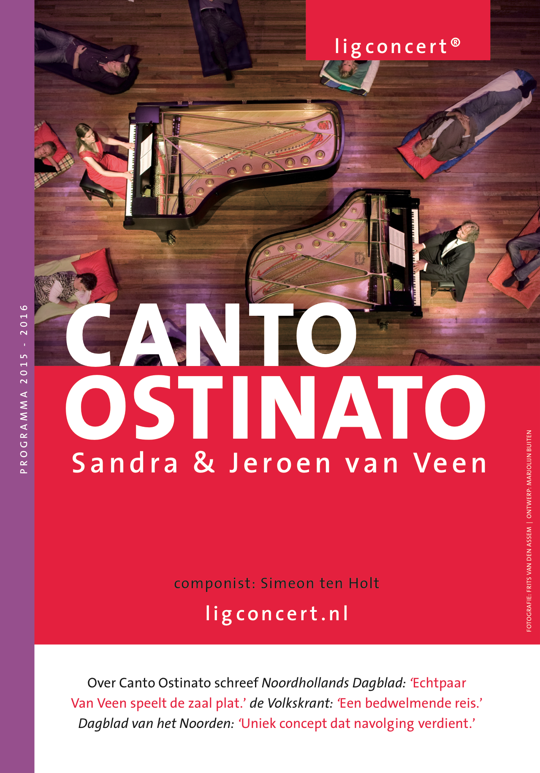

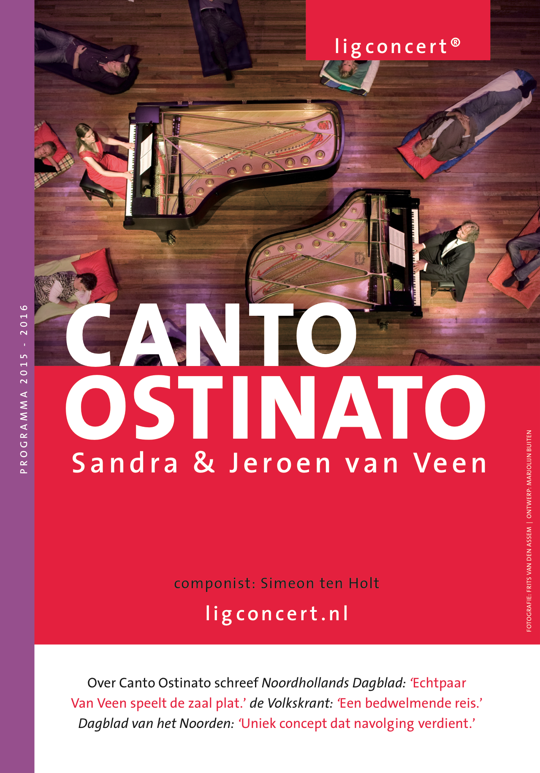

Canto Ostinato

Canto Ostinato

Playing time: from 90 minutes to 8 hours

Possible combinations we can offer:

Two Pianos or Keyboards

Three Pianos or Keyboards

Four Pianos or Keyboards

Five Pianos or Keyboards

Pianos plus Organ

Keyboard and Carillon

Pianos, Organ and Carillon

Pianos and Marimbas

Synthesizers

INDOOR or OUTDOOR performances possible

www.canto-ostinato.com

Pianos: Sandra & Jeroen van Veen, Fred Oldenburg, Elizabeth & Marcel Bergmann, Irene Russo

Organ: Aart Bergwerff

Carillon: Arie Abbennes, Frank Steijns

Marimbas: Esther Doornink, Peter Elbsertse, Nando Russo

Sandra & Jeroen van Veen performing Canto Ostinato in Arnhem (live Dvc+Cd recording)

Sandra & Jeroen performing Canto Ostinato in Novi Sad.

Sandra & Jeroen playing Canto Ostinato on two pianos in a tent by Dre Wapenaar.

Piano Ensemble in Utrecht, Railway station, on 5 grand pianos

Sandra Mol, Eka Kuridze, Fred Oldenburg, Tamara Rumiantsev and Jeroen van Veen on Fazioli Grand Pianos.

Piano-ensemble in Vredenburg, The Netherlands

Ellen Dijkhuizen, Fred Oldenburg, Jeroen van Veen & Kees Wieringa on four pianos

Tamara Rumiantsev, Sandra & Jeroen van Veen, 3 pianos

Jeroen & Sandra van Veen, Tamara Rumiantsev, 2 pianos

Peter Elbertse & Nando Russo, marimbas

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam 2002

Simeon ten Holt

Always the Same, Always Different: The Music of Simeon ten Holt

ALAN SWANSON

Most discussion of the music of Simeon ten Holt (b. 1923) comes out of or ends in his seminal piece for multiple keyboards,

Canto Ostinato (1976-79). This one will, too.

Ten Holt was born, and lives, in the artist colony of Bergen, in The Netherlands. His earliest musical enthusiam was for the piano, and this has remained throughout his compositional career and has been especially prominent in the last forty years. Instead of going to one of the great Dutch conservatories, he studied with a local composer, Jacob van Domselaer, who represented the musical side of the art movement called “De Stijl,” moving in 1949 to Paris for five years. There he studied with Arthur Honneger and Darius Milhaud, studies he describes as merely “decorative experiences, of absolutely no compositional importance.”

His return to Bergen in 1954 produced his first major composition, the “

Bagatelles” for piano, which constitute his first attempt to deal with then-current issues of tonality and atonality. To work through these problems, he developed a compositional process he called “diagonalism,” compositions informed by a chiastic structure centered on the tritone. This method resulted in pieces such as the

Diagonal Sonata (1959) and other similarly titled works. The 1960s also saw intensive experiment with serialism, a method he later abandoned, and extensive study of sonology, the nature of sound itself, which led to experiments with electronic music.

From 1970 to 1987, he taught contemporary music at the Academy for the Visual Arts in Arnhem. This was of central importance for his development as a composer. It was here he came to understand the position of music in a larger aesthetic context, when his students gave theatrical performances in which, at each moment, they themselves made all the performing decisions, a kind of

commedia dell’ arte with music. His breakthrough as a composer came at the Holland Festival of 1978, with a performance of his decade-old

..A/.TA.LON (an anagram of “atonal”), for mezzo-soprano and thirty-six playing and speaking instrumentalists. The performance the following year of his

Canto Ostinato for one or more keyboards and variable duration (at least half an hour) cemented his position as a leading Dutch composer. The 1980s and -90s saw further large works for multiple keyboards, all having several common characteristics: short sections, modified repetition, clear tonality, and a high degree of performer-decision.

There are not many orchestral works in ten Holt’s repertory, nor much vocal music, and there is not much chamber music, though there are two (early) string quartets and a string septet. For ten Holt, it all starts with the piano, the instrument that for him contains all the possibilities he needs. He says that his compositional method is first to set the whole piece in his head, after which he sits at the piano and works it out completely. Only when that is done does he finally put it on paper.

The

Canto Ostinato is not only his most-performed work, outside as well as inside Holland, it is a genuinely popular piece. Indeed, it is the most-popular piece of Dutch contemporary music ever, and recordings of it have sold more than those of any other piece of classical music in Holland. There are currently six differing dispositions of the music available in recording, for four pianos (several recordings), for two pianos (several recordings), for two pianos and two marimbas, for one piano, for organ, and for harp. The duration of each of these performances varies considerably, none lasts less than about an hour and some over two, though, oddly, ten Holt’s own reckoning is about thirty minutes.

My own encounter with

Canto Ostinato has been through the young Dutch pianist and composer, Jeroen van Veen, probably the leading exponent of minimalism in Holland today. He is a genial, energetic, and articulate advocate of ten Holt’s music and has performed his pieces from Miami, to Calgary, to Novosibirsk and most places in between, and in many spaces and instrumental combinations. One aspect of this music that particularly attracts him is its portability. By this he means that it can be performed almost anywhere one can put multiple pianos and people. Indeed, bringing music to the people instead of the other way around is one of his main goals as a musician. He and his wife, Sandra van Veen, have performed

Canto Ostinato in concert halls and in a tent (in the pouring rain, no less) made for that purpose by the artist Dré Wapenaar. Last November, together with three other pianists, they performed a version for five grand pianos in the main waiting hall of the Utrecht Railway Station. It will be performed this year in Amsterdam’s Organ Museum on two pianos and two organs. Though ten Holt says that his primary interest is in Time—“If there would be no Time, there would be no music.”—van Veen has shown that spatiality is a key element in the success of ten Holt’s pieces and, especially, of

Canto Ostinato.

I experienced this spatiality on a cold day late last December in the immense entrance hall to De Doelen, the main concert venue of Rotterdam. There, van Veen had assembled five pianos and twelve pianists, all between the ages, I would guess, of fourteen and eighteen, to do a short version of

Canto Ostinato, about one hour’s worth. This meant skipping many of the 106 sections of which the piece is constructed, which also meant deciding which ones to play and co-ordinating the sectional shifts, beyond which each player could decide upon his or her own phrasing, emphasis, expression, and volume, or, as van Veen puts it, “It’s more like being on a traffic-circle than at a corner with stop-lights where someone else tells you when you must stop or go.” Three pianists at each of four keyboards who, among themelves, decided when they would change-off playing (each played twice), took their cues from van Veen, and they were off. The electronic keyboards they had to use were, frankly, a grotesque parody of what a piano sounds like, but the youngsters were totally engaged in what they were doing. What was remarkable was that, though people were wandering about the hall and food was being sold and consumed, three or four hundred, young and old, not just parents and relatives, stood around, were attentive, and, through their listening, took part in what was being done. The applause was long and deafening, not just just because the piece was attractive and the children played well, but also because, for about an hour, a special community had been created of which they were also a part.

The music itself is simple, even tuneful. It was clear to me that the reaction was largely sensual rather than intellectual (apart from the general appreciation of the fact that it was children performing it well). It is, after all, a very sensuous piece: you don't have to know much about music to enjoy it. Part of the success in making such a community of performers and listeners lies in the very theatricality of the

Canto: it is, in its way, a very physical piece. Says van Veen, “When people listen to the

Canto, it is more like a ritual than a concert.” As he also pointed out, “The clarity of the

Canto Ostinato, only a 5/8 bar with a subdivision on 2 or 3, is part of the attraction. In addition, the piece evolves toward a charming melody that most people seem to recognize, although its DNA is hidden in the whole structure.” However, some of ten Holt’s other similar late pieces,

Lemniscaat (Infinity-sign, 1982-83) or

Meandres (1997), for example, strike me as working at a different intellectual level. I do not at all mean by this to underestimate the amount of intelligence it took to make the

Canto, but in some way, the art of

Canto Ostinato lies in the disguising of its art while making its structure absolutely obvious. The movement to each of those sectional changes, which usually bring about a key shift or some perceptible structural alteration, works on the listener in the same way as that great, brief, key change toward the end of Ravel's

Bolero (which, owing to its enormous popularity, and sensuality, may actually be the real foundation piece of 20th-century minimalism). Modern? The question doesn’t even apply. Here is a serious piece of contemporary music that reaches out to people across generations.

It would be easy to conclude from this that ten Holt is a one-work composer. It would also be easy to conclude that the very accessibility of

Canto Ostinato makes it a superficial piece. This would be greatly unfair. Though the notes of the

Canto are relatively easy, the piece as a whole contains plenty of knots and pleasures for players and listeners alike. The method he chose also gave ten Holt room to grow, as his subsequent pieces testify. His last work—he has stopped composing—

Soloduivelsdans IV (Solodevil’sdance IV, 1998), is a breathtaking virtuoso piano piece that would well grace a program of, say, Beethoven and Liszt sonatas. Simeon ten Holt may have saved the best for last.

.jpg)

.jpg)